Pink Zone Pillar #1: Cultural Self-Worth.

Society’s script shapes women’s health — when women are valued, they thrive.

What determines a woman’s health?

Hormones? Genetics? Access to care?

Yes—but the story is much larger.

A woman’s well-being is never in a vacuum.

It is deeply tied to her self-worth: her internalized sense of value, dignity, and agency. And this is largely shaped by how her culture reflects or diminishes her worth across her lifespan.

Does she have access to education?

Does she have equal rights to men?

Does she retain value post-childbearing years?

Does she have agency over her body, her finances, her choices?

Is she shielded from violence—or exposed to it daily?

These are not abstract questions.

These factors ripple directly into a woman’s physiology, stress response, resilience, ability to advocate for herself, to seek care, and ultimately impact her health outcomes.

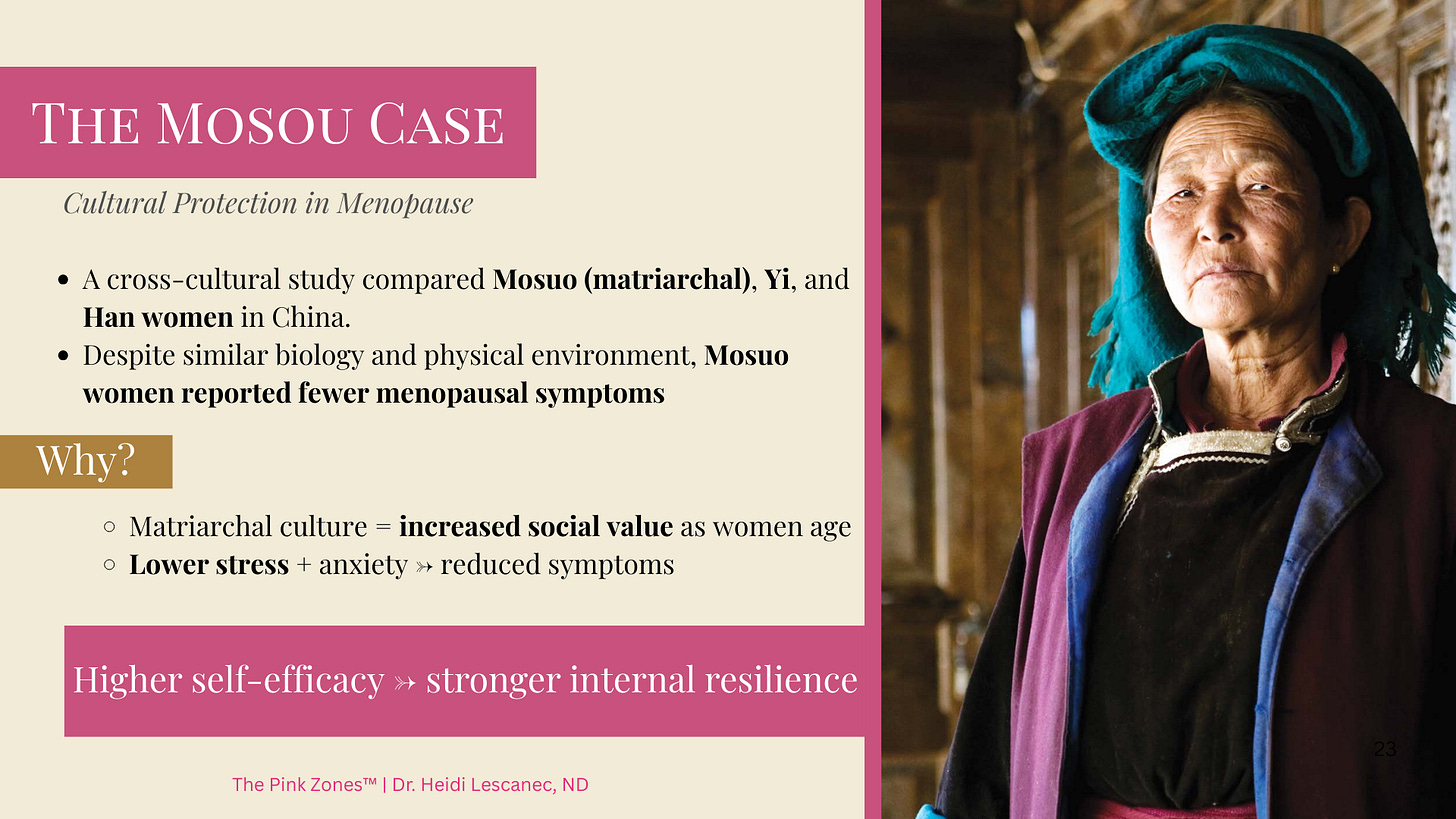

A Journey To A Modern Matriarchal Culture

To see this more clearly—(bifocals optional)—let’s step away for a moment and travel to the foothills of the Himalayas to Yunnan, China. Here live the Mosuo, one of the world’s few remaining matrilineal societies.

Among the Mosuo, women lead households, inherit property, and make key decisions. They practice what are called “walking marriages”: instead of a husband moving in, men visit partners at night but continue living in their mother’s household. Children are raised collectively in the maternal home, under the enduring authority of women.

As Mosuo women age, their value doesn’t decline. It increases. Older women become decision-makers, cultural anchors, and respected elders. Aging elevates their status, rather than erasing it.

Menopause Across Cultures

Why does this matter for health?

A recent cross-cultural study published in March of this year, (Gao et al., 2025) compared the illness conception and menopausal symptoms of Mosuo women with two neighbouring groups—Yi and Han Chinese women. All three groups share the same physical environmental conditions. Yet the health outcomes were starkly different.

Mosuo women reported significantly fewer menopausal symptoms.

Of the 11 main symptoms examined, these in particular were notably different : less insomnia, fewer hot flushes, reduced anxiety, less melancholy. The Yi and Han women—living under patriarchal norms—reported much higher symptoms overall (you can read the full fascinating study here).

Culture as a Protective Factor?

So why the striking contrast? Researchers suggest the key lies in cultural framing.

In the Mosuo context, menopause is not pathologized. It doesn’t signal a chaos state of impending decline and social recession. Instead, post-reproductive women are venerated as wise, powerful, and essential to the community.

This researchers suggest that this esteem—woven into daily life—creates resilience. Lower stress and higher self-efficacy buffer women against the very symptoms that, in the West, often feel overwhelming.

What this tells us:

Menopause severity is shaped by cultural context and resilience, not just hormones.

Biology might set the stage, but culture writes the script.

Where society honours women as they age, the body itself responds differently.

Bringing it back to Basecamp.

What does this mean for us? We can’t all move to the Himalayas or overthrow patriarchy overnight. But we can learn from the Mosuo.

If cultural self-worth protects health, then we must ask:

How does our own society value—or devalue—women. How about at midlife and beyond?

Do we treat aging as a diminishment or a part of growing up?

Do we listen to women’s lived experiences as seriously as lab results?

Do we create systems that support dignity, autonomy, and visibility across the lifespan?

This is the vision behind the Pink Zones: environments where women are rooted in self-worth, supported by systems, and uplifted by community.

When these conditions exist, the second half of life need not be a portal to a crisis—but a renaissance.

A Mentor Close to Home

Right here in Vancouver, British Columbia, where I live, one of my longtime heroes has been saying something very similar for decades—through the lens of endocrinology.

Meet Dr. Jerilynn Prior, a pioneering endocrinologist and professor at UBC. She founded the Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research (CeMCOR)—the first institute in the world devoted to understanding ovulation and cycles as central to women’s health.

Her career has been about flipping the script: insisting that women’s hormones be studied not as problems to be managed, but as vital forces supporting whole-person health. (This is so very naturopathic!) As Dr. Prior says:

“We have to value women’s experiences and stories just as much as lab results”.

Against a medical culture that has often been dismissive, sexist, and slow to change, she never wavered. She was among the first to champion bioidentical progesterone in perimenopause—long before it was accepted as more than just a uterine protector.

She has shown, for decades, that women’s health is not only biochemical. It is emotional, cultural, and deeply lived. And that listening to women isn’t just compassion—it’s science.

And at 83, she is still publishing, still challenging, and still rewriting the field.

In a recent chat with me, she described her upcoming memoir as “a feminist endocrinologist’s life story about discovering that ovulation and progesterone, in partnership with estrogen, are essential for lifelong health.”

Research Spotlight: Self-Worth and Cycles

Just a few weeks ago, August 12, 2025, Dr. Prior and colleagues published a prospective year-long study in PLOS One, (Shirazian N, et al 2025) tracking daily feelings of self-worth in 53 healthy premenopausal women, for over a year (over 698 menstrual cycles). The findings:

These data suggest that Feeling of Self-Worth is a trait that is stable within a person and changes little, if at all, related to women’s menstrual cycles and ovulation.

The narrative that women experience dramatic vacillation in mood and self-worth BECAUSE they are “on their period” is pervasive. But the questions need to be asked- is it the “menstrual cycle” or the hormones themselves that are to blame, and/or is it the conditions that disturb the healthy hormone cycling and ovulation.

It’s important to point out that the women in this study were ovulating at least at the beginning.

Normal ovulation indicates a healthy interplay of cycling hormones, especially sufficient amounts of progesterone production.

Dr. Prior speculates: “ovulatory disturbances such as short luteal phases (less than 10 days) or not ovulating (anovulation) occur when women are under physical or emotional stress related to inadequate nourishment, being physically ill, over-exercising, having insufficient energy intakes, or related to abuse, psychological conflict or depression/anxiety.”

In other words: self-worth is not solely influenced by hormones—it can be a stable trait, shaped by challenging life circumstances in combination with disruptions in biology (short luteal phases, not ovulating!)

I discovered similar findings when I dug into the research on the issue of depression during perimenopause- a time where progesterone production does decline (short luteal phases and anovulation are the norm here). It’s important to emphasize in this case, this is NOT a sign of pathology- this drop in progesterone is normal in the initial phase of the menopause transition.

I wanted to know: Is depression to be expected now that we even have an expected drop in hormones?

Research Spotlight: Depression and Menopause

We’re often told that depression in the menopause transition is inevitable.

But the data tell a more nuanced story.

A 2024 Lancet review (Brown L, et al. 2024) —one of the largest and most rigorous syntheses of prospective studies on mental health across the menopause transition—analyzed dozens of cohorts from North America, Europe, Australia, and Asia.

Here’s what it found:

• For women with no prior history of depression, only 10–30% experience symptoms.

• For women with a history of depression, the risk of recurrence is much higher—45–65%.

The key insight?

Hormones influence mood, but their impact depends on context—stress, inequities, and past vulnerabilities shape how women experience the transition. Sleep disruption or hot flashes don’t directly cause depression. It’s when these biological shifts collide with stressors that the risk escalates.

In other words, supporting women’s mental health is not only about providing effective and safe hormone therapy ( Yes, I prescribe hormones daily in my clinic, and have for decades!) But it’s ALSO about buffering the cultural and social contexts that amplify risks.

The larger thread + why it matters for you and me.

What unites the recent research findings, Dr. Prior’s work and the Mosuo women’s experience is a profound truth: when women’s worth is affirmed, health itself transforms.

Culture is not just background—it is biology’s partner.

It can either burden women with stress, stigma, and invisibility—or protect them with dignity, self-respect and agency.

Cultural self-worth isn’t a soft, abstract notion—it’s medicine.

Just as healthy mineral absorption and regular ovulation in “reproductive years” protect us against osteoporosis later in life, cultural self-worth protects women’s health across the lifespan.

The Pink Zones vision is simple: to create environments where every woman, at every age, carries that worth in her bones.

CITATIONS:

Gao L, Wang J, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Fu H. Psychological and cultural correlates of illness conception and menopausal symptoms: a cross-sectional and longitudinal comparative study of Mosuo, Yi, and Han women. Front Psychiatry. 2025;16:1496889. Published 2025 Mar 21. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1496889

Shirazian N, Shirin S, Kalidasan D, Prior JC (2025). Feeling of self-worth in healthy premenopausal women—relationships with menstrual cycles and ovulation over 1-year in the prospective ovulation cohort. PLOS One 20(8): e0327539. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0327539

Brown L, Hunter MS, Chen R, Crandall CJ, Gordon JL, Mishra GD, Rother V, Joffe H, Hickey M. Promoting good mental health over the menopause transition. Lancet. 2024 Mar 9;403(10430):969-983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02801-5. Epub 2024 Mar 5. PMID: 38458216.

OH MY GODDESS! This is phenomenal.

Does she have access to education? Maybe.

Does she have equal rights to men? Absolutely not, except in the micro-culture you've educated me about today

Does she retain value post-childbearing years? NOPE, barely. Even in a wealthy country such as the US. NOPE.

Does she have agency over her body, her finances, her choices? Are these rhetorical questions with the same answer to make a point?

Is she shielded from violence—or exposed to it daily? Oh, yes, I guess they are.

Brilliant, Dr. Heidi. Thank you.

This is so important for women to hear and absorb!